The Landscape of Fear

The landscape of fear defines the innate risk/benefit analysis conducted by prey animals in a given area of the landscape: how safe they feel grazing based on the presence of predators and the topography. How long do they need to remain eat sufficiently before moving and how effective is a route for escape? The landscape can be thus a source of fear and this fear keeps grazing animals on the move, makes certain areas ‘out of bounds’ and allows the landscape to recover naturally.

The UK is one of the most nature-depleted nations on earth, largely as a result of urbanisation and the use of remaining countryside for agriculture and ‘sporting’ pursuits (hunting and shooting). Rewilding has been proven to be a key aspect of decarbonising our environment and slowing the pace of climate change and several discrete initiatives are at the movement’s forefront; notably Coombeshead in Cornwall and Knepp in West Sussex. As well as beavers and other extirpated (locally extinct) species, lynx and - most totemic and polarising - wolves, are essential to rewilding. These keystone species are essential components of any ecosystem; something cannot be even remotely ‘wild’ or in balance without the presence of critical species of animals at key parts of the food chain. In this case; the over-grazing and stripping of carbon-absorbing natural forest will continue without the presence of apex predators to keep deer moving through the landscape. As for sheep? They can be protected, as happens in many countries around the world, but that costs money and reduces profit margins. In the case of many farmers operating on the breadline because of price-fixing by large retail chains, that is a real-world problem.

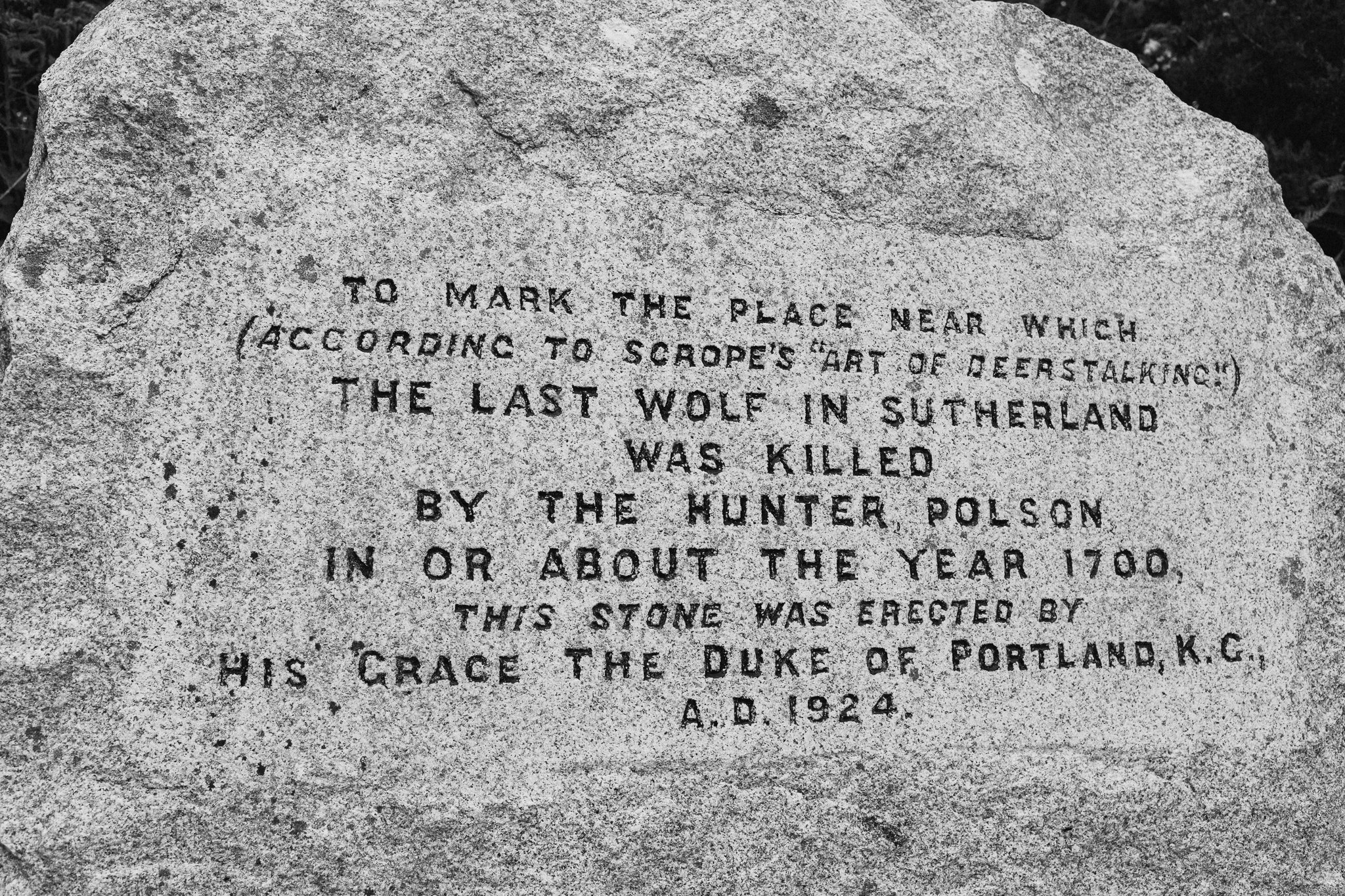

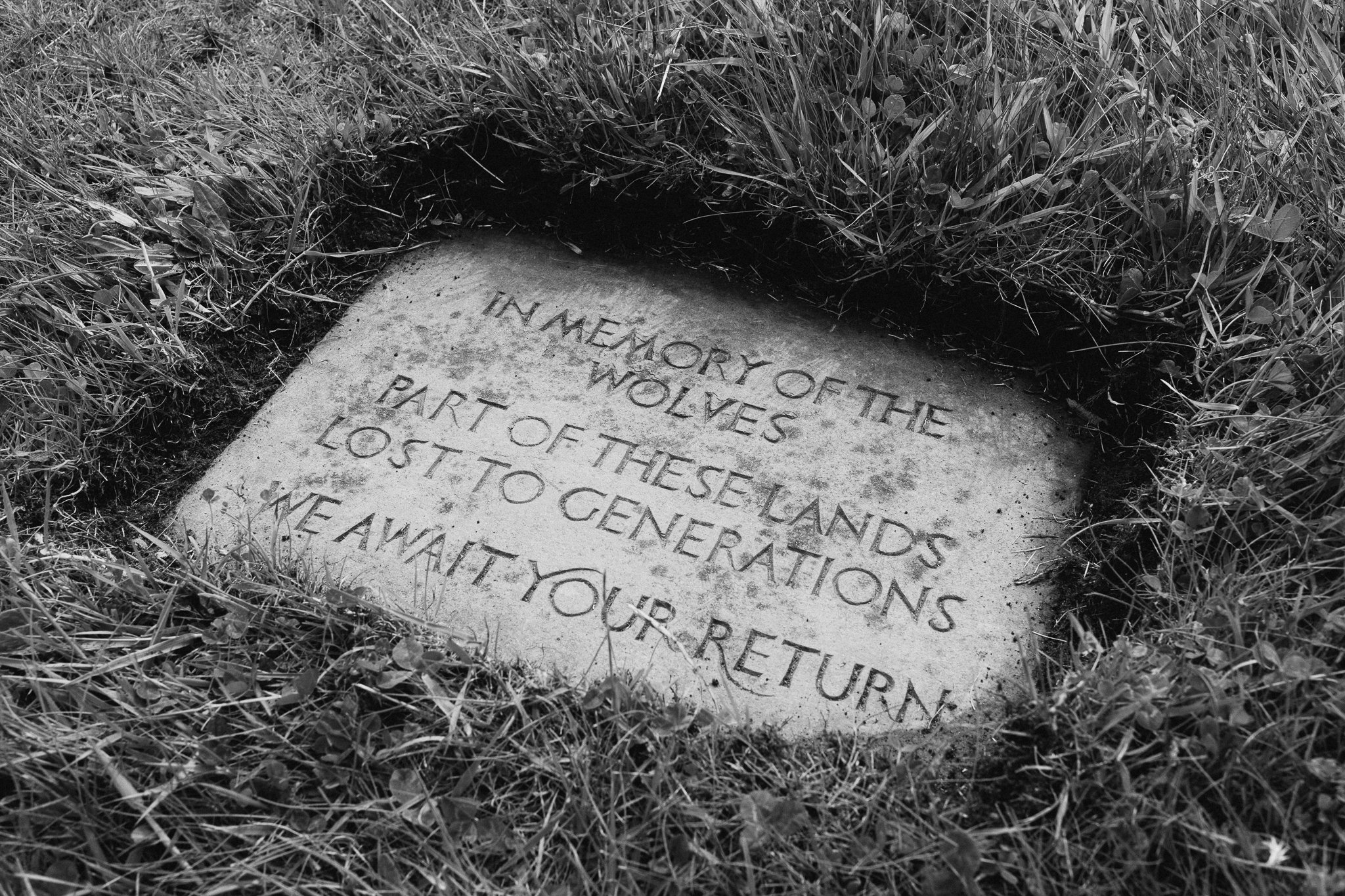

As part of this work I have so far journeyed to north east Scotland to visit the “Wolf Stone’, a tablet erected (now in a lay-by next to a dog waste bin - very apt) on the A9 in Sutherland. It ‘commemorates’ the approximate location of the killing of the last wolf in Sutherland in the 1700s. A young stonemason, Beatrice Searle, carved and installed a riposte immediately opposite the wolf stone on the grass verge. I also found the site of an old wolf pit ( a baited trap dug into the ground) at Moy. But the landscape of the wolf is everywhere. They exist in Normandy but are seldom seen by the people who live there.

Even in the highlands of Scotland, it was notable that despite the landscape appearing to be ‘wild’, it is anything but, having been altered by centuries of over-grazing by sheep and the stripping and killing of young trees by deer. Both species irrevocably changed Scotland after the highland clearances, when Scotland was effectively turned into a playground for English nobility. Only 2% of the ancient Caledonian forest remains today as a direct result.

I want to look at the arguments that surround rewilding via its most evocative symbol, the wolf. Notably most opposition to its reintroduction is industrial-scale farming and downsides founded on little but folklore and hysteria; as such our own landscape of fear. This work is ongoing.

With thanks to Derek Gow, conservationist, writer and founder of Coombeshead, Professor Danielle Schreve (in her capacity as former head of Quaternary Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London) and Beatrice Searle, carver and stonemason.